-by Lemuel J. Lim, LL.B.(Hons)(UK), LL.M. (UK), LL.M Tax (US).

How do you use the cash flow method to value a small business? This article gives a simple explanation. If you are unsure whether the cash flow method is right for you, see the first article in our firm’s series on How to Value a Business for Purchase or Sale.

Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) Valuation

There are many types of cash flow analyses. This article focuses on a modified version of a discounted cash flow method (DCF) that is relatively simple and arguably the best for valuing a small business. The main objective here is to learn the basic concept. Once you understand the concept, it will be easier to teach yourself and understand how other variations and methods of discounted cash flow analyses work.

DCF valuation is about making predictions concerning how much future free cash the business will generate, and then “discounting” the future cash flow back into today’s money. We do this so that we can determine the current value of the business. In other words, we are looking at the money the business will make in the future and “converting” the value of how much that is worth to the buyer in today’s money. The concept is based on the assumption that cash in a person’s hands today is worth more than cash in a person’s hands tomorrow. If we gave you an option of receiving $1,000 dollars today or $1,000 in 3 years. Which would you choose? We hope your answer is that you would choose today! Money today is more valuable because you could, for example, invest that money and receive even more money in 3 years.

Step 1: Understand Past Financial Statements and Business Operations

To make a projection of how much free cash a business will generate in the future, we have to understand what free cash has been generated in the past. To do this, we need a good understanding of the business’s operations (how it generates cash, and what the money-making drivers are). We also need to be familiar with past financial statements. Lastly, we need to think about what assumptions we are going to make when we predict how much cash the business will generate in the future.

When calculating free cash flow, there are two approaches. The first is called the unlevered cash flow approach. This is the free cash flow available to all stakeholders including debt holders. It is a more common approach for large deals.

For sales of smaller businesses, levered cash flow is typically a more common option as it provides a rough snapshot of what the new owners will get after the debt holders receive their interest expense.

Step 2: Determine and Discount the Future Free Cash Flow

Always bear in mind what we are trying to do in this step. We are trying to find out how much cash will be left over each year after all the expenses (including cost of goods sold, operating expenses, overhead expenses, interest and tax expenses, etc.) have been taken into account. It is the cash that is not needed to run the business and can be returned to the owner without affecting the business.

Thankfully, if you have calculated the Seller’s Discretionary Earnings (SDE) as shown in our previous article on valuing a business based on earnings, then in most scenarios, we can more or less use SDE as an approximation of free cash flow. To be more precise, the SDE we have gone through in our previous article is the approximation for the levered free cash flow.

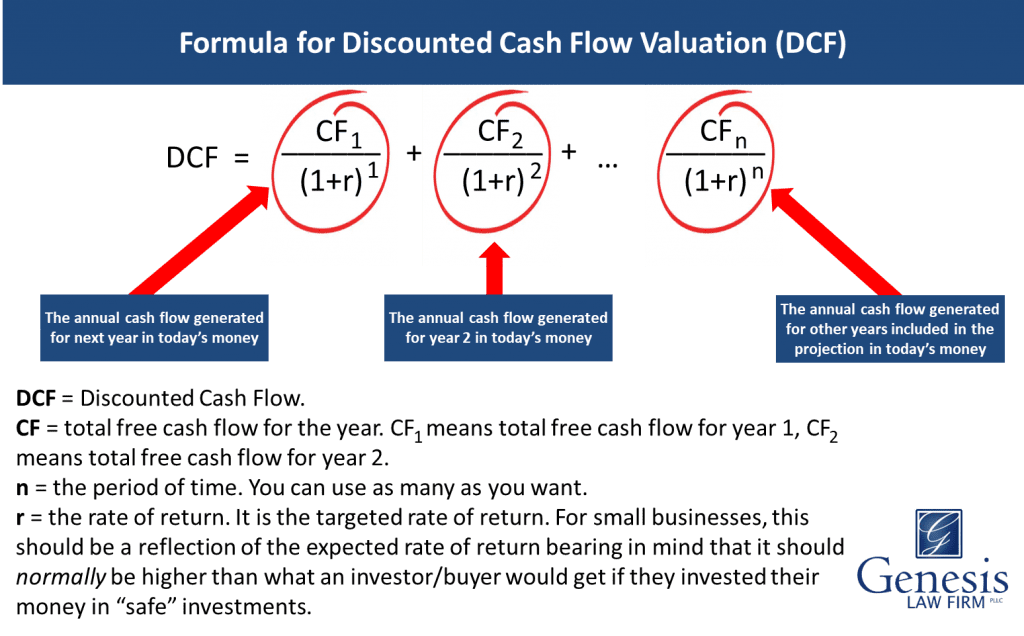

Future projections for cash flow are typically in the range of 5-10 years. Once projections are made, the valuation formula for DCF is:

A preliminary question you will need to ask is whether DCF is the right method to value the business. Sometimes, it is not. If you think that, you should raise it with the other side with an explanation, especially if they are trying to use this method to negotiate with you. That said, the DCF method can be useful in many different kinds of situations. Perhaps the most useful applies to the scenario where the target business is a newer business with high-growth potential, but is currently not yet profitable. This scenario is often the case with highly innovative companies like tech startups.

One important point to note here is the “r” in the diagram above. This rate of return (“r”) is the discount rate used to calculate how much less the future cash flow is in today’s money. For larger businesses, the discount rate is usually calculated by using something called WACC (Weighted Average Cost of Capital). Don’t worry about this! It is not possible to calculate WACC because small, privately owned businesses do not have market capitalization.

So what should the discount rate (“r”) be? There are ways to approach this for small business transactions. The starting point is to understand that “r” is a reflection of risk the buyer is willing to take. Theoretically, there are two components to this risk:

- The “risk free” rate of return. If you invested your money with US government securities, the textbook answer tells us that this is “risk free.” The government can supposedly just print money to pay its debts. The “risk free rate of return” is usually linked to the return of a long-dated US Treasury bond.

- The “risk premium.” This is the premium over and above the “risk free” rate of return for investing in a commercial business.

There are many different factors that make up the risk premium:

- if the business is not a public company,

this calls for a higher discount rate; - if the business is a smaller company, this

calls for a higher discount rate; - certain high risk industries will result in

higher risk premiums; - anticipated inflation will impact

the adjustment of risk premium; - certain company-specific risks will result

in higher premiums. These include factors such as:

(i) low revenue growth trend;

(ii) financial risks in the

business;

(iii) high operational risks in

the business;

(iv) downward profitability trends

in the market;

(v) concentrated customer base;

(vi) product over-concentration;

(vii) saturated market;

(viii) weak competitive position;

(ix) poor quality of management;

(x) poor quality of staff;

(xi) who the buyer is (big company

lower premium, small company higher premium).

As a guide or even as an alternative to the above, if there are industry guides / reports / public research that show market trends and average-industry growth rates, these could also be used a point of reference to calculate the discount rate.

Step 3: Assign a Terminal Value

After you have chosen the selected period to project cash flow, you now need to assign what is called a “terminal value.” The terminal value represents the cash flow received by the business after your projected period.

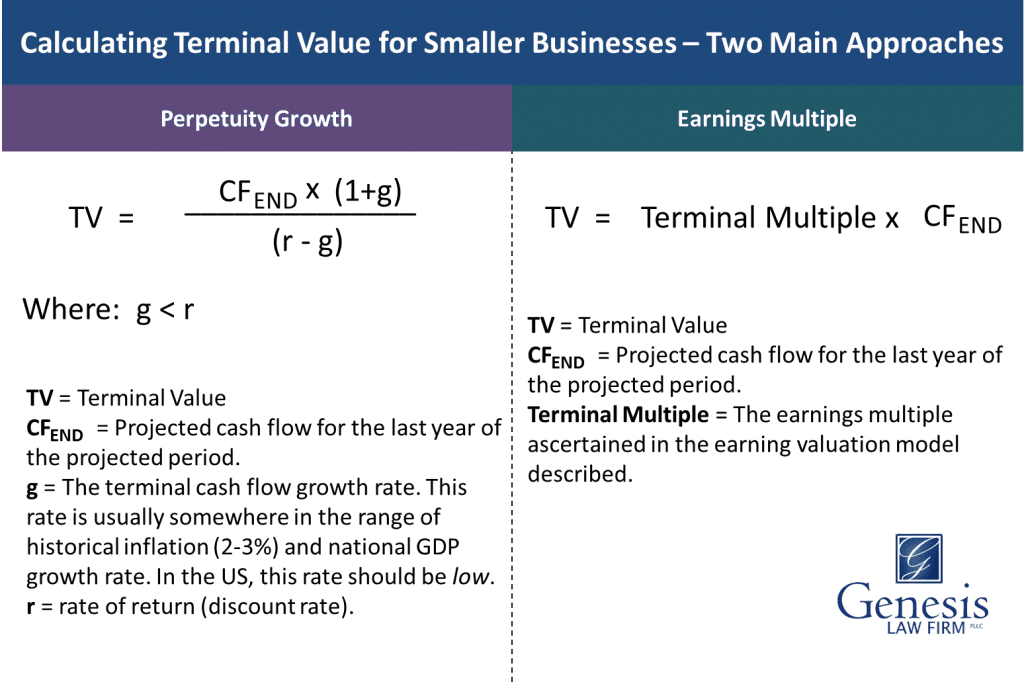

There are a number of different ways to approach this, but the first two listed below are the main approaches:

- The “perpetuity growth” method. This

method assumes that the business’s free cash flow will grow indefinitely at a

particular rate. We give you our own version of the perpetuity growth model

which is more relevant for smaller businesses. - The “earnings multiple” method. This

method assumes that at the end of the projected forecast, the business will

“exit,” meaning that the business will be sold again or listed as a public

company, and a valuation is required at that point. - The “future liquidation” method. For

asset heavy businesses, this method assumes the company will be liquidated

after the projected forecast and measuring each future asset’s market value

less the liabilities to gain a definite value. This is a very case specific

scenario that may only be appropriate for some types of businesses. - Ignore terminal value and assume cash flow

declines to zero. The projected forecast is extended for another period

of time to show a decline of cash flow to zero. The free cash flow for this extended

period is calculated in the same way shown in Step 2 above. This method is

appropriate where a party thinks that the business is not a “going concern” (a business that will not last indefinitely). The good thing about this approach is that

you don’t have to worry about terminal value. The bad thing about this approach

is that you are left with the headache of coming up with a forecast period for

how long it will take before the cash cow dies. Expect questions from the other

party!

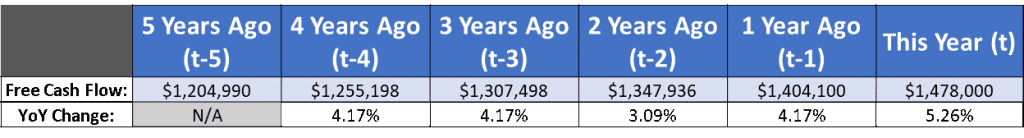

Example: Sophia wants to see how much Exodus is worth using the cash flow method of valuation. She has already opened up the company’s books and records to calculate the SDE for the past 6 years. She wants to use that as the rough approximation for free cash flow:

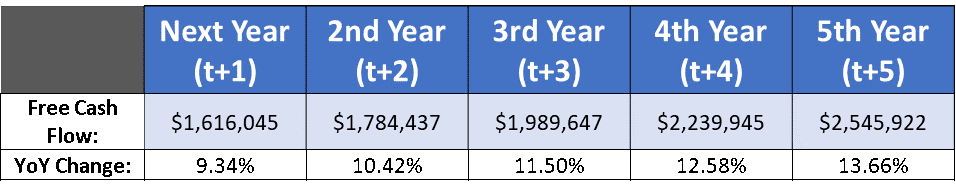

Sophia can see that although, on average, the company’s cash flow growth rate for the last 5 years is approximately 4.17%, she knows that in the last 3 years, the business has been on a steady and consistent rise. She is able to attribute this to online viral fads for quirky toy unicorns that have made its way to the United States from Asia. She is confident she can justify an increasing year-on-year cash flow growth forecast:

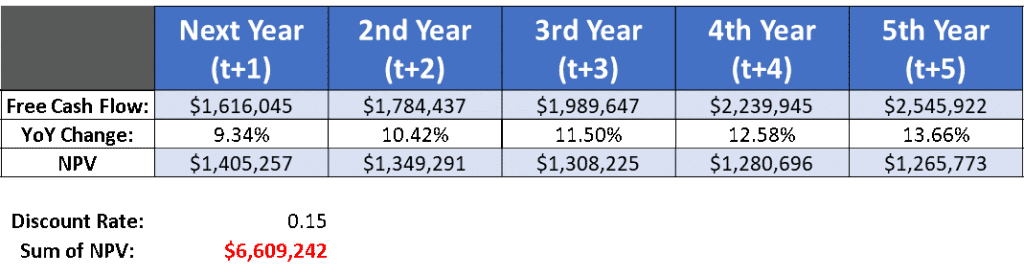

Sophia now wants to calculate the discounted cash flow valuation for her projections. She begins by trying to work out what the appropriate discount rate should be. First, she looks at the “risk free” premium rate and decides to reference the yields on US 10yr Treasury bonds. On average, US 10yr yields have been approximately 2.1%. She knows that her discount rate should not be equal to or lower than this rate. She then determines the risk premium. Luckily for Sophia, she is an active member of the American Fantasy Toymaker’s Association, an industry representation group that regularly publishes statistics concerning the subsectors within the industry. She can see that aggregated returns for her fast-growing sector is 15% (significantly above the 2.1% risk free rate). Now that she has her discount rate, she calculates the net present value (NPV, or “future money valued as of today”). The sum of the NPV for the projected 5 years of cash flow is then added up to make a single number as shown below:

Now Sophia must calculate the terminal value. She decides to calculate terminal value using the “perpetuity growth” method. For the “perpetuity” method, she begins by making an assumption on the terminal cash flow growth rate. She takes this to be historical inflation, say, 3%.

Terminal Value = ($2,545,922 x 1.03) / (0.15 – 0.03) = $21,852,497

Sophia adds the DCF valuation for the next 5 years to the Terminal Value and arrives at the following valuation:

DCF Valuation of Exodus = $6,609,242 + $21,852,497 = $28,461,739

Post-Calculation Note: The Private Company Discount

As you can see, the DCF valuation model in our example scenario has come up with a pretty “punchy” number. If you have been following the calculations closely, it is not hard for a person to come to understand that the DCF method can potentially be fatally flawed. The most common flaw is that it is grounded in assumptions and financial perceptions that are prone to human error and unrealistic party biases. These are often “magnified” in the formula. We therefore encourage you, whether you are the seller, or the prospective buyer, to look at the DCF method with your eyes wide open. A mindset to have when looking at DCF is to remember the following facetious motto:

“If you put trash into the formula,

expect to get trash out“

Returning to the given example, perhaps Sophia, our hypothetical seller, knows that a $28m+ DCF valuation is going to cause prospective buyers to walk away in disgust. Thankfully, with smaller, privately held companies, what often happens is that the parties will negotiate a “private company discount” that will apply to the final valuation number. This discount is typically expressed as a percentage figure ranging from 20% to 50%. The private company discount can be used as a negotiating tool so the parties can arrive at a valuation number that accounts for the additional perceived risks involved in buying a smaller business.

We hope you found this article helpful. Our firm believes in making quality information available online free of charge; and, in that vein, we’ve written on numerous related topics. We encourage you to visit our firm’s business resource page.